OTTAWA, July 5, 2016 – Environmental assessment, the amalgam of consultations and regulatory decisions that governments must conduct to approve or turn down natural resource projects, is now on the front lines of reconciliation between Aboriginal peoples, governments and resource developers.

Author Bram Noble, in a new paper for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, lays out what’s working and what needs to be improved so Aboriginals can participate fully in EA.

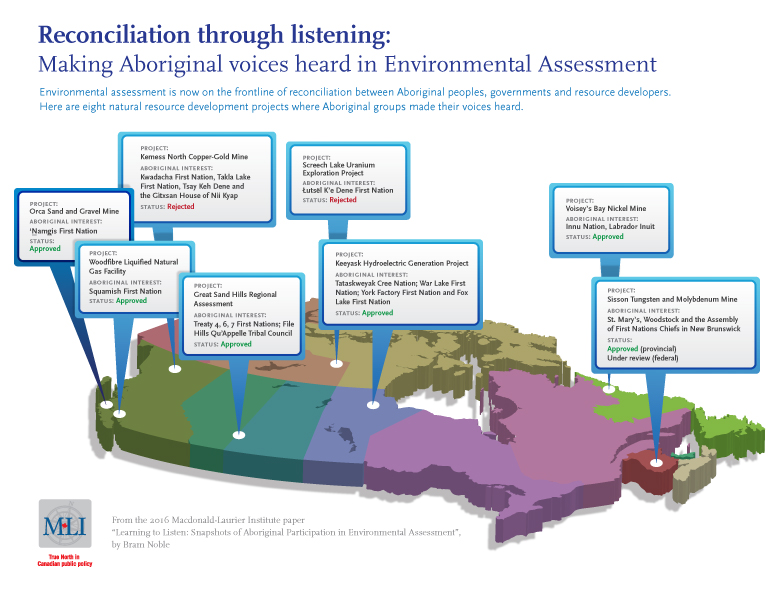

The paper, which examines eight different case studies of past Aboriginal EA participation, is particularly timely given Ottawa’s recent announcement that it will be reviewing the EA process.

The paper, which examines eight different case studies of past Aboriginal EA participation, is particularly timely given Ottawa’s recent announcement that it will be reviewing the EA process.

To read the full paper, titled “Learning to Listen: Snapshots of Aboriginal Participation in Environmental Assessment”, click here.

Noble finds that EA is no longer simply a technical tool, reviewing the science of a particular project to ensure it won’t harm Canada’s environment.

It is now, given the extent to which Aboriginal groups have become full participants in the natural resource economy, one of the primary means by which First Nations and other indigenous peoples make their voices heard on participation in big economic projects.

Thanks to highly-publicized Aboriginal protests against specific projects, a common perception has taken hold that Aboriginal people in Canada are opposed to natural resource development writ large. The EA process, in this way of thinking, is shutting out most Aboriginal groups.

Bram Noble finds that the prevailing narrative is wrong: While the process has been far from perfect, there are numerous instances where Aboriginal groups are being heard through the environmental assessment process.

Not only that, they are also using it as a means of getting involved in projects that are helping Aboriginal peoples contribute as full participants in a natural resource economy that is now creating a path to prosperity for a slew of Indigenous groups across the country.

For example, as of June 2016, there are 79 federal EAs in Canada. Most of these, which include examples of Aboriginal groups working within the EA process, get drowned out by more controversial projects.

For example, as of June 2016, there are 79 federal EAs in Canada. Most of these, which include examples of Aboriginal groups working within the EA process, get drowned out by more controversial projects.

But there are still many lessons to be learned. Noble’s eight case studies, which include projects that were both rejected and approved, hold important lessons for improving EA so it better reflects Aboriginal views.

The Orca Sand and Gravel Mine on Vancouver Island, for example, engaged early on with the ‘Namgis First Nation. This resulted in the integration of Aboriginal values in the terms of reference for the EA, a project design that was considered appropriate by the Aboriginal community, and a working relationship that was maintained post-EA through ongoing impact monitoring programs.

Meanwhile, with the Woodfibre LNG Facility in British Columbia, the Squamish Nation EA process, the first by a First Nation in British Columbia, operated independently of, and parallel to, the provincial and federal EA processes for this project. It resulted in an improved project design and, arguably, facilitated provincial and federal EA approvals.

The benefits of Aboriginal participation in EA are numerous, including improvements in project design, the integration of new knowledge about potential impacts, discovering new ways to mitigate environmental damage or social impacts on communities, the potential for greater collaboration, and increased legitimacy of development undertakings. There is no magic bullet that will assure better practice in all project and decision-making contexts, but more collaborative EA processes that empower Aboriginal peoples are more likely to result in better outcomes for both the project proponent and the Aboriginal community.

***Bram Noble is a professor of environmental assessment at the University of Saskatchewan.

Download the full report here“